Sydney Modern: the ultimate cultural cringe

By JUDITH WHITE

On Saturday 3 December Sydney Modern, the controversial new building at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), will open with a fanfare of publicity and a nine-day festival. The public unveiling has been preceded by private previews with flutes of champagne and guest lists featuring PR flunkies and Liberal Party supporters. At one, on Tuesday 29 November, Premier Dominic Perrottet proclaimed the edifice to be “the most significant cultural build since the Opera House”. In the heart of the building visitors will find themselves in the Aqualand Atrium, which represents an unprecedented concession of corporate naming rights within a public institution. As CEOs, media and ministers party, the rest of us across NSW are left wondering: “Who pinched our Gallery? And who’s paying for this extravaganza?”

The green space on the harbour is gone, the architecture will be debated for years, and a big question mark hangs over future funding. But on the opening weekend the lavish celebrations will be led by dancing drones, the well-heeled Board of Trustees and members of the moribund NSW Coalition Government, which has funded $244 million of the advertised $344 million construction cost.

Heading the public relations push for the project is the Sydney Morning Herald (SMH), newspaper arm of Nine Entertainment which is chaired by former Liberal federal Treasurer Peter Costello. Its editor, Bevan Shields, took the unusual step on 25 November of writing a “Note” to readers lauding the project and accusing its critics of cultural cringe and of not being “proud of our institutions”.

That’s a bit rich. The term “cultural cringe” could more accurately apply to the other side of the controversy. There was the insistence by the Gallery’s board and management on commissioning overseas architects SANAA who, however eminent and accomplished, may not have been fully briefed on the area’s environment, climate and millennia of history. Then American landscaper Kathryn Gustafson was allowed to override the concerns of commissioned First Nations artist Jonathan Jones about the land bridge between the two buildings. And not least, both Coalition State Government and Gallery management largely ignored the detailed, well-documented objections to the plan from many of the State’s eminent environmentalists, architects, museum specialists and arts professionals. Key issues among these critics are that the siting and architecture of the new building do not respect the heritage of the Royal Botanic Gardens or the Gallery’s original neo-classical Vernon façade; and that large parts of the building are more suited to a function centre than to an art museum.

The lost green space seen from the front of the original Gallery

The slur against the objectors comes from the same Bevan Shields who, since his appointment to the SMH editorship one year ago, has already been obliged to issue two defensive apologies. The first, on 4 March, was for reporting that the State Government’s lockout of transport workers was a strike. The second, on 12 June, concerned columnist Andrew Hornery’s ultimatum to actor Rebel Wilson about his revelation of her same-sex relationship. The editor’s Note on this, according to The Monthly columnist Martin McKenzie-Murray, “made things much worse”, with its “creepy blandness … robotic tone and defensiveness”.

Perhaps Shields’ next apology should be given to critics of Sydney Modern – preferably without the aforesaid “creepy blandness” etc.

The Vernon façade of the AGNSW – overshadowed

The looming issues

A building alone is not guaranteed to put Sydney on the international cultural tourism map. That’s wishful thinking on the part of Trustees and Government. The factors that count are (1) the quality and care of a gallery’s collection; (2) its ongoing exhibition program, and (3) adequate recurrent funding on which both care of the collection and good programming depend.

At a Budget Estimates hearing in the NSW Parliament on 5 September – just three months before the grand opening – Gallery director Michael Brand was asked about operational funding. On paper the budget allocation for the Gallery looks like a substantial increase, following some smaller increases over the previous four years, and totals $71 million for Financial Year 23. But Dr Brand told the committee: “It’s made up of a number of issues, including some cash flow issues with the construction, so it’s not all actually operating budget.”

Cash flow issues with the construction? Pardon me? Is this a polite term for cost blow-outs? It would be highly unusual for a NSW Government infrastructure project not to exceed projected costs. But just as the business case for Sydney Modern has never been revealed, its actual cost has yet to be disclosed. The total was projected to be $344 million, $100 million of which the Gallery has raised from benefactors.

Under further questioning at Budget Estimates Dr Brand said: “My figure for actual recurrent, which I guess would be sort of pure operational costs, is 41 million and the previous year it was 39.5 million.” That doesn’t even come close to meeting inflation – in other words, it’s a cut.

So how do you run an institution that’s doubled in size on a reduced operational budget? The Gallery claims that it has been able to bring on more staff. Dr Brand told the previous year’s Budget Estimates, in 2021: “Roughly doubling the size of the building does not mean you have to double the size of your staff. There are no offices in the new building but there will, of course, be more security, more visitor services and more cleaning, for example.” But the Public Service Association (PSA) put on record that its members at the Gallery were asking for an increase in permanent jobs in crucial departments including installation, registration, curatorial, conservation, public programs and education. The union request was treated with contempt.

What makes a great public gallery?

The departments specified by the PSA are essential for the AGNSW to restore its reputation for excellence and attract enough visitors to pay its way. A projection of two million visitors a year was mentioned in the planning stages. In the current atmosphere of global economic and climate crises, that projection looks less and less realistic. Beyond the initial spike of visitors curious to see what all their taxpayer dollars have built, everything will depend on the programming.

And that programming has been under heavy criticism in recent years, not least from the SMH’s own art critic, John McDonald, who has been somewhat sidelined in the paper’s pre-opening publicity blitz. On 9 June, commenting in his weekly newsletter on the scandal over Dr Brand’s expenses, he wrote that the episode “would be less of an embarrassment if the AGNSW could point to years of brilliant success under his leadership. Instead, the gallery has been in slow motion when it comes to exhibitions, which have frequently done without catalogues or openings … Meanwhile, staff have been herded into open plan offices – a piece of discredited management-think guaranteed to diminish the standard of work, while the executive élite have their private offices.

“The Trustees have been complicit in all this lazy, wasteful stuff… The state government too, has created a fertile environment for running up ‘hospitality’ expenses, by expecting the AGNSW to raise such a large amount of funds privately. This is virtually an invitation to wine and dine mates and prospective sponsors on the public purse. It’s high time governments rethought their eagerness to palm off arts funding to the private sector, and accept that culture is not a privilege or a luxury but an essential service.”

NSW Coalition’s “legacy”

Australian governments have long thought of their legacy in terms of bricks and mortar. Both State and Federal Coalition Governments of recent years have behaved like ministers from Rob Sitch’s Utopia on steroids.

Powerhouse Ultimo – on the brink of destruction

Whatever you think of Sydney Modern, the case of the Powerhouse Museum is considerably worse. $840 million has been spent on the construction of an entertainment venue in its name on a flood plain at Parramatta, and on the dispersal of Australia’s finest collection of applied sciences, housed until now in the custom-built museum at Ultimo. The Powerhouse Ultimo has been a state-run science, technology and design museum catering for a broad audience of all ages and backgrounds, but is now to be turned into a fashion venue for Sydney’s well-to-do, while its priceless exhibits are either buried away in storage out at Castle Hill or scattered to the four winds.

The latest report of the NSW Upper House committee on museums, chaired by Robert Borsak MLC, described the decision to relocate the Powerhouse as “a thought bubble that became government policy without any real evidence base”.

The Powerhouse Museum Alliance has vowed to continue a last-ditch campaign for the restoration of the collection. Leading NSW museum specialist Kylie Winkworth warns in a recent paper against Premier Perrottet’s empty 2020 promise that Powerhouse Ultimo would be saved. Rather, she writes, the $500 million so-called Ultimo Renewal scheme for a fashion and venue centre is a “cynical continuation” of the demolition plan. Her grim conclusion: “A 142-year-old museum is now on the brink of extinction.” Which must be a world first, though not of the kind for which the NSW Coalition would like to be remembered.

On the most conservative estimates, since 2015 the NSW Coalition Government has spent between $1.5 and $2 billion on cultural infrastructure. That amount of public money could have built two key institutions. One would have been a satellite of the AGNSW in the Western suburbs, which are crying out for such a facility. While Sydney Modern gives politicians and corporates a function centre on the harbour just a stroll across The Domain from Macquarie Street, the biggest concentration of NSW citizens face an arduous trip that most will think twice about attempting. The other institution which would fill a serious gap in the State’s cultural infrastructure is a museum of Aboriginal history. Its creation would be a vital contribution to the process of truth-telling so essential to the nation’s future. There would have been enough spare change from those two projects to give the Powerhouse at Ultimo a perfectly adequate upgrade.

But the horse has bolted. It is doubtful whether any State government in the immediate cash-strapped future will be quick to allocate similar amounts for new buildings. The question remains whether, by the time of the State election next March, the incoming government of Premier Chris Minns and his team will have learned the lessons of the Coalition’s mistakes and will develop cultural policy driven by the public interest. That means a focus on proper ongoing funding of the sector, rather than vanity projects.

Meanwhile, as a mood for change sweeps across the nation, the opening of Sydney Modern may well serve as a last hurrah for the Perrottet Government. The top end of town will be quaffing champagne while the rest of us will be thinking: “What’s happened to our State’s public gallery? It’s been hijacked!”

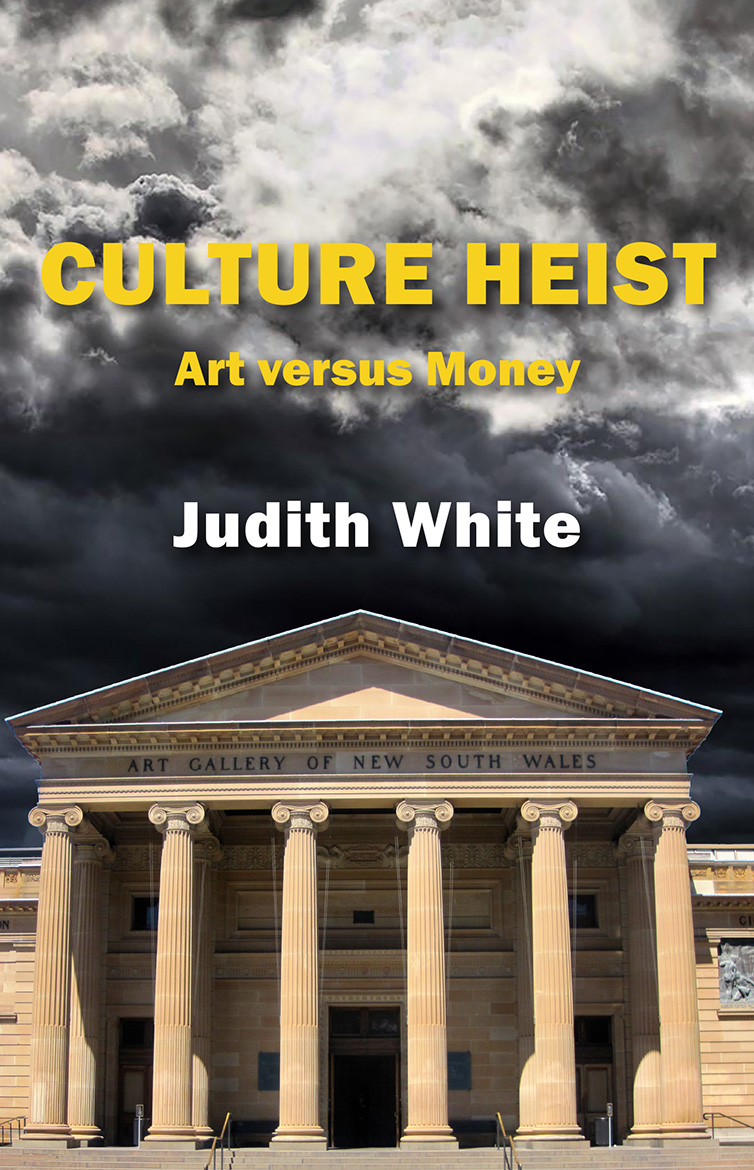

The book that ignited the controversy

The book that ignited the controversy

Culture Heist: Art versus Money by Judith White (Brandl & Schlesinger, 2017) gives the background to the Sydney Modern project and the corporatisation of the arts. Order online HERE – where White’s memoir Children of Coal is also available.

Sydney Modern – or Sydney Migraine?

1 DECEMBER – Two highly qualified writers on architecture review Sydney Modern. “The worst public building in Sydney” – Annie Godfrey, sustainability specialist. “Profoundly mistaken climatically as well as conceptually” – Philip Drew, architectural historian. Read them in full HERE.

Thanks Judith,

My lasting memory will be that of a little girl chasing a foraging magpie on that part of the Domain lawns which has been built on, while her admiring parents enjoyed the harbour view from a strategically sited park bench

Thank you Judith for pulling together the stands of this planning fiasco. The Sydney Modern function centre is built on Sydney’s most significant park lands, preserved for the public since the early 1800s. Whatever people think of the architecture, it was still a mistake to filch these park lands belonging to the public, held in trust by the Royal Botanic Gardens. The development has destroyed what was the garden’s most sensitive transition, that feeling of release as you pass over the bridge to the tunnel of green. That’s gone forever from public enjoyment, replaced by a bus bay. The only reason Sydney Modern is there is because that’s what the gallery’s donors wanted. That was Michael Brand’s response when asked why Sydney Modern wasn’t going to ‘remote’ Walsh Bay – or heaven forbid Parramatta. Hundreds of millions of taxpayers’ dollars have been spent to indulge the wishes of the gallery’s donors for views over Woolloomooloo. Millions more in recurrent funding will follow. It was a mistake not to give the communities of Western Sydney a choice in whether Sydney Modern should be at Parramatta or the ‘Western Parkland city’ which has had no cultural infrastructure investment. It’s still a mistake that what passes for cultural policy making in NSW has entrenched cultural disadvantage when we have inexplicably ended up with two contemporary art museums in the city centre, but no major public gallery between the city and Penrith. David Borger, who has built his public profile decrying the cultural funding deficit in Western Sydney, has said nothing about the millions spent on Sydney Modern, or Walsh Bay or the Sydney Opera House. He has his prize in the big event centre under construction in a high risk flood zone at Parramatta. After the AGNSW showed how to grab a big slice of Sydney’s Domain, the question is whether Sydney’s citizens can defend the Domain from further land grabs masquerading as cultural developments. With the way the power is exercised behind closed doors in Sydney that may be unlikely.

Excellent comment from one who really knows about cultural institutions.

Agree with your comments.

Disgraceful to destroy that open space in the first place but then to create a jumbled series of art shelters thrown randomly onto the side of a hill at enormous cost and by architects who clearly have no appreciation or understanding of the locale or the locals is beyond disappointing. They had an opportunity to do something spectacular. Look, I’m no academic, writer or aesthete and comparisons are odious but I’ll say it anyway….ride that ferry along the river to MONA and there’s a sense of drama unfolding and you’re not disappointed from the moment you set foot on land to the moment you get off the ferry on the return trip. It’s full-ball excitement, blood, sweat and tears, wonder, awe, joy etc and largely BECAUSE OF THE BUILDING and the smart AUSTRALIAN architects that created it.

Maybe I’ll feel differently after visiting Sydney Modern (if I can find my way around) but from the air things don’t look promising.

At the end of the day though Judith, the regions are the incubators of art and I’m very proud of our local yapang gallery (formerly Lake Mac Gallery) which is producing excellent exhibitions (the Peter Gardiner show was exceptional and one of the best I’ve been to) plus we have mima our new multi purpose gorgeous white art cube (designed by an architecture student) which sits beautifully in one of our lovely parks. With these on our doorstep the trip to Sydney for art is losing relevance….

Congratulations to the yapang gallery – and agreed about MONA.

For an institution whose raison d’être is visual delight and meaning, I cannot work out how they came up with such an ugly set of boxes on that harbourside slope. The views from the air (as per a previous comment) make it clear: it’s a totally unsympathetic addition to the contours (however altered from pre-1788) of that part of Sydney Harbour. The alienation of huge areas of the Botanic Gardens is a scandal, another example of a supine government trust fudging its charter when under pressure from Macquarie Street. As for the SMH, under Bevan Shields, it is buttering its readers up for its editorial on Saturday 25 March 2023: this Government deserves a fourth term. Shields loves the new gallery, exhorts us to cherish our major cultural institutions, yet, under his watch, the destruction of the Powerhouse at Ultimo is, in the pages of the Herald, apart from the occasional dissenting letter, apparently OK. How dare Shields claim that people like me with deeply-felt negative views about Sydney Modern are part of some ‘cultural cringe’. How low can a newspaper editor go in insulting someone who has read his paper for nearly 70 years? Shameless. Finally, anyone, politician, bureaucrat, cultural CEO, trust president, trust member, architect, heritage council member, journalist, who refers to what is happening at Ultimo as a “renewal” should be consigned to the dustbin of cultural Newspeakers.

Thank you for this excellent comment. Bring back delight and meaning!