By JUDITH WHITE

My Uncle Dick was a Manchester electrician and lifelong trade unionist who survived the Thai-Burma railway in World War Two, but never afterwards joined a military parade or wrapped himself in the Union Jack.

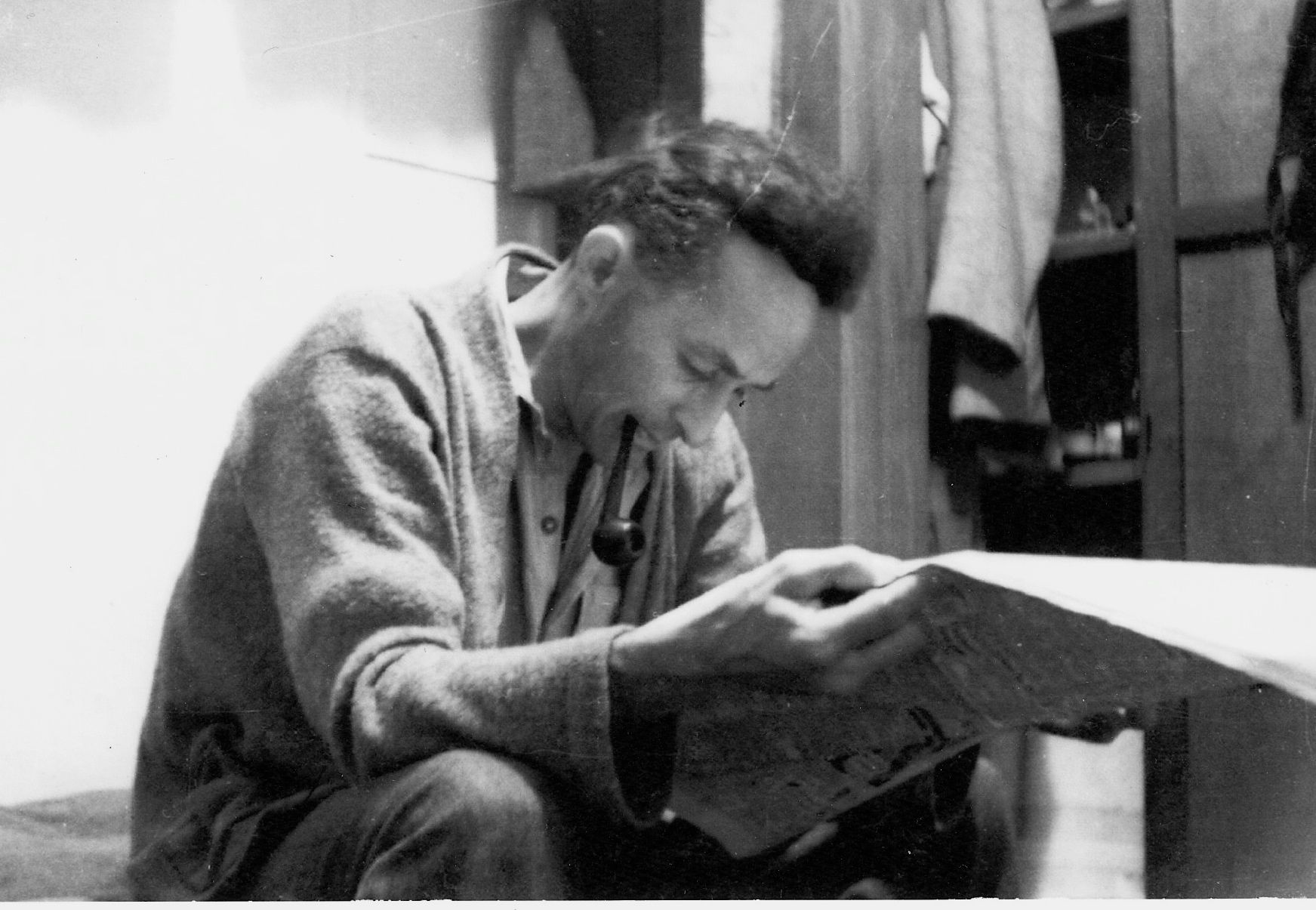

His prisoner-of-war diary, previously unpublished, forms part of my memoir Children of Coal, and it’s tough reading. But my earliest memories of him are all peaceful. I was three years old when he started visiting us at our house on the Lancashire coast, as he recovered from his bouts of malaria, and I would sit on his knee as he read the Manchester Guardian and smoked his pipe.

Many years later he gave me his wartime diary. He had never left Lancashire before he signed up for army duty in 1941. He shipped out of Liverpool to Singapore, which the British government under Winston Churchill surrendered to the Japanese in February 1942, abandoning Dick and his comrades to be taken prisoner by the Japanese Army.

ORDER ‘CHILDREN OF COAL’ ONLINE – SEE BELOW

After months in Changi prison my uncle was among the Allied POWs taken to work for almost three harrowing years on the Death Railway. In one diary entry he writes of having trench feet, malaria and dysentery all at once: “Tents are sodden and we are all crawling with lice as well. Dr Mac our MO didn’t know whether to feed me for malaria or starve me for dysentery so he decided to give me small doses of arsenic.” He lost all the fingernails on one hand, but with no painkillers “just had to grin and bear it”. The Australian medic, almost blind from malnutrition, sewed up his foot with an old needle and fishing twine. Dick credited the Aussie POWs with helping him stay alive; they “stick together when in trouble” in a way the class-ridden British troops did not.

A great cricketer and soccer player in his youth, by the time Japan surrendered Dick was down to about 47 kilos in weight. From the hospital ship home he wrote to his mother reassuring her, and hoping – ever the Manchester man – that his work tools would still be all right.

In the early 1950s he spent some time working his way round Australia, for whose people he retained a lifelong affection, before returning home to be married. The photograph above shows him reading the paper in the camp at the work site for construction of the Kwinana oil refinery outside Perth.

He worked as an electrical engineer all his life, retiring to live on the moors at Hebden Bridge, and died in 2001 at the age of 86.

Britain’s abandonment of Singapore signalled the end of its empire east of Suez, five years before India’s inevitable independence and 15 years before Malaysia’s. It’s ironic that, in its doomed efforts to revive the myth of imperial greatness, the UK is now part of the lamentable AUKUS anti-Chinese pact, hanging on to the coat-tails of the US and dragging Australia with it. I think my Uncle Dick would have been pretty scathing about that.

THEY ALL READ THE PAPERS

Harry Sutton, proof-reader

In Britain as in Australia, war and empire brought nothing but suffering to working-class families. Some of my own North of England family continued, despite everything, to believe in Queen and Country. But it was their lives, more than their ideas, that turned me into a socialist and an internationalist. With age, I have come to realise how much I owe them all, and in my memoir I have tried to do them justice.

To order your copy of Children of Coal click here.

Leave A Comment