In 2007 the Australian Public Service Commission published a set of guidelines entitled Building Better Governance. Under the heading “Clear Accountability Mechanisms” it stated:

“Australian Public Service agencies are accountable to the general public through the Parliament as well as to the Government. The success of relationships that agencies develop with stakeholders, including the public, is affected by the agency’s reputation of integrity, openness and accountability. On a practical level, stakeholders need to trust that decisions affecting them are made consistently and openly, and that they will be dealt with in a consistent way by all parts of the agency.”

In line with these recommendations the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), for example, regularly publishes the minutes of its monthly Monetary Policy meetings (as does the Bank of England and the US Federal Reserve).

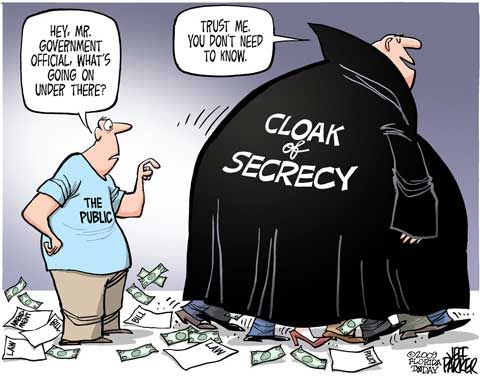

But the proceedings of the boards of most of the country’s cultural institutions, which are also public service agencies, remain a mystery to the public.

Why? One standard argument is that discussions of bids or negotiations for acquisitions to the collection are commercial-in-confidence. Fair enough – but these can easily be redacted.

Almost 18 months ago leading arts administrator Michael Lynch openly criticised corporate leaders on arts boards which fail to stand up to government spending cuts. It’s hard to see how matters have improved since then. And because their deliberations remain secret, there’s no evidence that they even discuss ways to oppose cuts imposed by Federal and State governments of all persuasions. Small wonder that the goodwill of stakeholders has been eroded.

Almost 18 months ago leading arts administrator Michael Lynch openly criticised corporate leaders on arts boards which fail to stand up to government spending cuts. It’s hard to see how matters have improved since then. And because their deliberations remain secret, there’s no evidence that they even discuss ways to oppose cuts imposed by Federal and State governments of all persuasions. Small wonder that the goodwill of stakeholders has been eroded.

The fact is that in public institutions, boards are answerable ultimately to the public. And in some New South Wales institutions in particular, there appears to be a resistance to the level of transparency you would think the voting public has a right to expect.

How in fact are arts boards held accountable? Their most important public documents are their annual reports, which are statutory requirements. In addition, by custom and practice, their strategic plans are generally available. Let’s look at what these tell us about the two NSW institutions at the centre of so much controversy – the Powerhouse Museum and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Annual reports – Delivered to the relevant government, these are essential measures of performance. But they are also PR exercises and pitches for government funding, so they need to be read with care for matters not highlighted. Take the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (MAAS), which includes the Powerhouse Museum. The President’s Foreword to its 2015-16 annual report gives scarcely a hint of the furore surrounding its proposed move from Ultimo to Parramatta, merely saying it has “prompted widespread community discussion”. Delve down further and the report itself gives the lie to some of the arguments government supporters have made for the move – for example, the supposed decline in visitor numbers to Ultimo. In fact numbers at the Powerhouse had increased by 33%. (For an excellent myth-busting of some of the arguments concerning the Powerhouse move, see submission no 142 by former deputy director Jennifer Sanders to the NSW Upper House Inquiry into Museums and Galleries.

The annual reports of the Art Gallery of New South Wales also bear careful reading. The fine print reveals that while the number and cost of senior executive positions has more than doubled since the end of Edmund Capon’s directorship five years ago, visitor numbers have stagnated. In addition to the cost of executive salaries, the Art Gallery spend more than $1.5 million on consultancies – about four times as much as the highly successful National Gallery of Victoria. It doesn’t add up to a great argument for successful expansion.

The Boulton & Watt beam engine

Strategic plans – The Powerhouse comes under the MAAS strategic plan, which emphasises the need for care and innovative use of its exceptional collection. Strange, then, that the board seems to have given so little thought to the massive costs of moving the Powerhouse collection to Parramatta. It took submissions to the Upper House inquiry by former leaders of the institution, including the one mentioned above, to bring this to light. Rather than addressing the issue, the strategic plan for 2017 to 2022 sidesteps the issue of location with a waffly motherhood statement: “The Museum’s collection is not bound by time or place; rather it seeks to represent and encompass human creativity in all its expressions to tell a story of innovation, imagination and ingenuity.” One wonders when it will dawn on the board that something as substantial as the steam-powered 1785 Boulton and Watt beam engine is not off in a cloud somewhere but, like many other treasures of the collection, is quite emphatically bound by time and place.

At least the MAAS strategic plan can be found on its website. The AGNSW in Capon’s day used to have one, but I recently searched the Gallery’s website in vain for the latest version. Then it dawned on me. The Sydney Modern expansion project is the strategic plan. In an arts institution, it seems to me, if your strategy is a building, you’re in trouble. What about the art?

Time for transparency

My previous blog focused on the risks of expansion at the AGNSW without a commitment to increased recurrent funding from government. Gallery supporters are left with no idea how the ongoing operating costs of the new building are to be met. Meanwhile the existing, much-loved building is expected to absorb further cuts in funding year-on-year. It’s high time for the NSW government and the AGNSW board of trustees to release the Sydney Modern business plan so that there can be full public discussion of how the expansion will work.

Consultation is essential to building trust in institutions. Under great pressure, the government has at last convened two public meetings about the proposed Powerhouse move. They will take place on July 26 at the Parkroyal Parramatta, and on July 31 at the Powerhouse in Ultimo, both at 6.30pm. They have not been widely advertised and to attend you need to register here .

At the AGNSW there has been no such open consultation in the four years since the Sydney Modern project was announced. The most we are promised now, according to the Gallery website, is that “the final design concept will be shared with the public for further feedback as part of a State Significant Development Application planned to be lodged in the coming months.”

The budget allocation of $244 million for Sydney Modern should signal the end of the secrecy surrounding the business plan for the project. But it’s not happening. Staff and volunteers are still bound by a draconian code of conduct to say nothing that could be construed as a criticism. Questioning voices in media risk being excluded from particular programs: for the past 18 months, art critics Christopher Allen and John McDonald have been banned from giving lectures or taking art tours for members of the Art Gallery Society, among whom they are hugely popular.

Their criticisms have on the whole been quite measured. In reviewing current exhibitions at the AGNSW John McDonald felt obliged to write, in his weekly blog: “I’m not trying to be unduly ‘negative’ with the AGNSW. I’m expressing a sentiment shared by many people I speak with, who feel let down by the gallery. The quality of exhibitions has become so dismal over the past few years that management needs to stop obsessing about the Sydney Modern project and deal with the present.” You can bet he won’t be asked back to lecture or lead tours any time soon.

One of the most disturbing examples of the lack of transparency concerns the Art Gallery Society, the friends’ organisation which has given the institution incomparable support over the years. Members are not allowed to know what is in the Memorandum of Understanding signed a few months ago between their governing Council and the Gallery.

Some years ago a member attending the Society’s AGM asked Councillors for an assurance that members’ funds would not be channelled away from supporting the collection and be used to fill the gaps in the Gallery’s operating budget. At the time, the assurance was easily given. Now the question needs to be asked again.

The need for independent voices

The land bridge over the Cahill Expressway

The voice of the Art Gallery Society is being stifled. Nominally it remains independent; effectively we are witnessing a takeover by stealth. But that’s a mistake. An independent membership organisation can be of great assistance in putting pressure on government to get a better deal for the arts. In the late 1990s when the Eastern Distributor was being built, the Society was instrumental in campaigning for the land bridge which now protects the Gallery from the noise and fumes of the freeway.

In his recently published memoir Setting the Record Straight Carl Scully, former NSW roads minister in Bob Carr’s government, recalls authorising the land bridge and waxes indignant that in 2013 the Gallery’s new director Michael Brand “proposed a $450m Pharaonic redevelopment right on top of the open space I had proudly left for the people of Sydney”. (The website Inside Story has a review of Scully’s book .)

The proposal has now been quietly modified to leave the land bridge clear, but the issue of green space remains and is still championed by the Foundation and Friends of the Royal Botanic Gardens – a valiant body of the kind the Society used to be.

There’s much more to be said about importance of membership organisations as independent voices in the arts, and this blog will return to the subject in the coming weeks.

Sidney Nolan and Randolph Stow

In search of something more elevating than the latest shenanigans in NSW, in recent weeks I’ve been re-reading the works of Randolph Stow. I’ve been thinking about the day I met him, 25 years ago, and about his connection with Sidney Nolan. They were friends, collaborators and masters of modernism who saw the Australian landscape in new ways. My article about them is here on the Nolan Centenary website.

Latest reviews of Culture Heist

Grace Cochrane on the Powerhouse Museum Alliance website calls the book a “clear exposé of the shifts in government and bureaucratic values from benefits to audiences and concern for collections, to economic and political returns”.

In a critical review on ArtsHub Gina Fairley writes: “I do encourage a read of Culture Heist for anyone working in the visual arts. These have been complex times and this book might just offer a road map to understanding our new world – a map that extends well beyond the impressive columns of the Art Gallery of NSW.”

Leave A Comment