Stories of indigenous and Palestinian lives

Melissa Lucashenko Edenglassie UQP, October 2023; Sara M Saleh Songs for the Dead and the Living Affirm Press, August 2023

BOOK REVIEW by Judith White

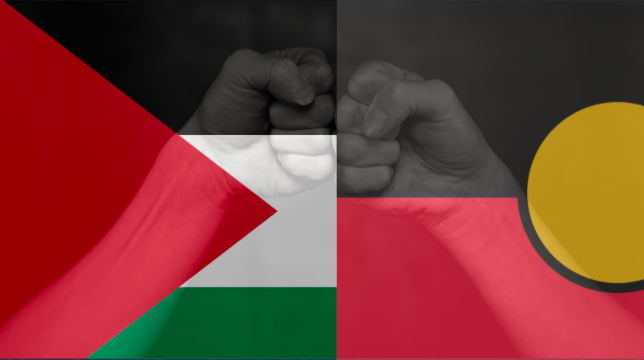

For peoples dispossessed by colonialism, living under constant threat to their identity and their very existence, culture is not a luxury or a “lifestyle choice” – it’s key to survival.

Two outstanding new novels by Australian women from very different backgrounds bring home this truth. At a moment when Australia has cruelly rejected constitutional recognition of First Nations peoples, and Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank are suffering the most murderous Israeli attacks in decades, they make timely reading.

Melissa Lucashenko is a Miles Franklin award-winning Aboriginal writer of Goorie and European heritage. Sara Saleh is a human rights lawyer and a poet, winner of both the Judith Wright and Peter Porter prizes, and is of Palestinian, Lebanese and Egyptian descent.

From the other side of the frontier

Melissa Lucashenko

Edenglassie is Lucashenko’s most profound work yet. Set in what are now known as the Gold Coast and Brisbane (“Edenglassie” if the Scots had their way), it opens our eyes to the realities of indigenous lives lived and lost under British “settlement”.

The novel moves between the mid-19th century and today. It has a dual beginning. In modern Brisbane, elder Granny Eddie suffers a fall and is ignored by white passers-by until a group of overseas students come to her aid (something that really happened to singer Aunty Delmae Barton, mother of musical maestro William Barton). In recovery, she begins to see and hear presences from the past.

Back in 1854 at Jellurgal (Burleigh Heads) a young Yugambeh boy named Mulanyin learns to fish and to love Country before being sent north to a clan at Woolloongabba where he will witness the white colonists begin to assert their dominance over the more numerous Goorie. Through it all, the connection to Country is described in compelling detail.

Amid the subsequent chapters on the loss of rights, freedom and lives, two love stories shine through. Mulanyin longs to take his new love Nita back to his home country; Granny Eddie’s feisty activist granddaughter Winona (shades of Lucashenko’s acclaimed Too Much Lip) meets a doctor trying to reclaim his own past.

Amid the subsequent chapters on the loss of rights, freedom and lives, two love stories shine through. Mulanyin longs to take his new love Nita back to his home country; Granny Eddie’s feisty activist granddaughter Winona (shades of Lucashenko’s acclaimed Too Much Lip) meets a doctor trying to reclaim his own past.

Transcending both romances is the resurgence of memory across five generations. Lucashenko weaves together the historical and contemporary stories towards a climax which in less skilled hands might seem fantastical, but here is entirely natural.

For this novel the author spent many hours listening to surviving elders of the region. Their oral history, filtered through all the years of massacres, dispersal, “assimilation” and the Stolen Generation, has now been given literary form by a storyteller of distinction. Australian fiction is replete with tales of white settlers. Edenglassie is a masterpiece from what historian Henry Reynolds calls “the other side of the frontier”.

Poetry in exile

Sara Saleh

Songs for the Dead and the Living is poet Sara Saleh’s first novel, and gives voice in turn to the suffering of generations of Palestinian exiles. It’s the story of Jamilah, growing up in Lebanon, then forced to flee to Cairo with ther family in her teenage years when Israel invades, civil war erupts and thousands of Palestinians are killed in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps.

Egypt presents new challenges. Its citizens are disposed to welcome their Palestinian cousins. Its government, under recently-elected President Hosni Mubarak, is increasingly repressive, siding with Israel’s principal backer, the United States. As her family and friends come under pressure, Jamilah eventually leaves for Australia.

That is the political background. In the foreground is the coming-of-age story of a young girl close to her beloved sisters and orphaned cousin, and respectful of parents struggling to adapt to rapidly-changing conditions. She is drawn to people who love books; she looks beyond the boundaries of the traditional life her mother clings to, closely observes the colour and movement of the city streets, has a secret longing to make pictures and keeps a camera hidden.

As in Lucashenko’s story, it’s the grandmother who provides the golden thread of identity. Jamilah’s Teta Aishah had fled her home during the Naqba – the catastrophe of 1948 when the British turned Palestine over to Zionist terror gangs who killed 15,000 Palestinians, drove 750,000 more into exile and seized their lands and homes. While the girls’ parents focus on adapting to their host society, Aishah will never let them forget that they are Palestinian. Jamilah grows up reading Mahmoud Darwish and other Palestinian poets.

As in Lucashenko’s story, it’s the grandmother who provides the golden thread of identity. Jamilah’s Teta Aishah had fled her home during the Naqba – the catastrophe of 1948 when the British turned Palestine over to Zionist terror gangs who killed 15,000 Palestinians, drove 750,000 more into exile and seized their lands and homes. While the girls’ parents focus on adapting to their host society, Aishah will never let them forget that they are Palestinian. Jamilah grows up reading Mahmoud Darwish and other Palestinian poets.

Saleh’s novel clearly draws on her own family background. It’s a story full of love – of memories of the land and of lost homes, of hours spent in the family kitchen making traditional food, of secrets shared with sisters and of grief for those lost and disappeared. It should be read by everyone wanting to understand the long trauma of Palestine.

Australia’s place in the world

A week after the No vote in the October 14 referendum, acclaimed actor/director Rhoda Roberts wrote: “I will continue to dedicate my life’s work to ensuing there is always a platform to tell the stories, celebrate the language and enable the songline its rightful place through the consistency of our custodians and cultural authorities. So, we will keep thriving – gathering and creating…”

The survival and extraordinary renaissance of the world’s oldest living culture should be Australia’s great gift to the world – not submarines and Washington’s warmongering rhetoric. And as a multicultural society Australia should also celebrate the work of Palestinian exiles, instead of repeating the propaganda that masks genocide.

Each of these books is a significant contribution to making us a better society. I cannot recommend them highly enough.

Thank you Judith for once again highlighting the stories of our humaneness…and the complex emotional scaffolding within each of us.

Such stories touch the roots of so many and hopefully extend greater compassion, tolerance and perception.

Thank you, Kim. In these troubled times we need not only these stories, but your music. Thinking of you.

Characteristically timely, culturally sensitive reviews when we all need signs of courage after the awful negativity of the Voice referendum and in the shadow of Israeli, US, European , Australian leaders/ apparent pleasures over genocide in Gaza. Thank you Judith for briefing a wide public about these special books.

Thanks, Stuart, for your own recent posts, especially this one: https://johnmenadue.com/western-governments-responsible-for-carnage-in-israel-genocide-in-gaza/