This summer’s Australian bushfires, says Sir David Attenborough, signal a crisis point for Earth. They also signal a crisis point in the ideological struggle within Australia over the future of the country and the world we live in.

Scrambling to repair his prime ministership from the damage done by his negligent response to the catastrophe, Prime Minister Scott Morrison is out to focus debate on how we “adapt” to climate change, not how we mitigate it.

To allow this would be a terrible betrayal of the victims of the fires and of the millions of young people whose futures are at stake. Limiting discussion is a tried and tested technique of neoliberalism, perfected over the past four decades. As American intellectual Noam Chomsky puts it: “The smart way to keep people passive and obedient is to strictly limit the spectrum of acceptable opinion, but allow very lively debate within that spectrum.”

I have become wary, in this context, of the term “culture wars” as applied to public life in Australia. It implies a certain moral equivalence, as though there were a contest between legitimate arguments.

The reality is different. On the one side, there are the Big Lies. On the other, there is historical truth, attested by the sciences and expressed in a myriad of ways in the arts – more on the arts below.

There is no shortage of Big Lies but there are three crucial, interrelated ones to be combatted at this critical moment in the life of the country.

Big Lie No.1 – Colonisation was peaceful

The story goes that pre-colonial Aboriginal society was “primitive” and simply collapsed before the superior settler system. This is the modern version of terra nullius, the racist British colonial doctrine that the country was unoccupied before 1788. Terra nullius was knocked for six by the Mabo decision of 1992, but the true history still struggles for acceptance despite being well established in scholarship.

More than 300 massacre sites mapped by the University of Newcastle team

First, the evidence is clear that “settlement” was in fact invasion. In a lifetime’s work, much of it summarised in his 2013 book Forgotten War, Professor Henry Reynolds has shown how colonialism waged war on Aborigines and how they resisted. More recently, Professor Lyndall Ryan of the University of Newcastle has released a comprehensive map of the massacres of Aboriginal peoples across the country. Second, thanks to writers like Bill Gammage and Bruce Pascoe, we now know that Aboriginal societies were far from “primitive” and had developed way beyond hunter-gathering. It’s becoming widely accepted that First Nations people have much to teach the rest of us about fire management, but there is far more to be learned than that.

Pascoe’s revelatory book Dark Emu, first published in 2014, has gradually become a bestseller and a children’s edition was published last year. Since plans were recently announced for Blackfella Films to make it into a TV series, Pascoe has been subjected to an outrageous campaign of vilification. The book was denounced by right-wing propagandist Andrew Bolt, and when that fell flat in came Josephine Cushman – PM Tony Abbott’s appointee to the Indigenous Advisory Council, and his greatest fan – to cast aspersions on the author’s Aboriginality. Busy fighting the bushfires round his home near Mallacoota, he nonetheless responded with his habitual dignity. And as he earlier said: “We stab out our eyes rather than regard Aboriginal achievement in this country.”

Nailing the lie about colonisation means accepting the 2017 Statement from the Heart so cruelly rejected by then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, and putting in place a Makarrata Commission to begin the process of truth-telling and healing. Books by Reynolds, Pascoe and others should take pride of place in all school history syllabuses. And there must be recognition of those brave indigenous people who died resisting the only invasion Australia has experienced.

Big Lie No.2 – Australia’s wars have all been fought for “freedom”

Every life lost in Australian wars fought overseas is also an undeniable tragedy. But the tragedy is compounded by the way governments and media glorify those wars. Half a billion dollars is allocated to expanding the Australian War Memorial when other key cultural institutions – including the National Gallery, National Library and National Archives – are being starved of cash. Public money is poured into Anzac Day celebrations and, via the Department of Veterans Affairs which should be using the money for veterans, into school programs that make the slaughter at Gallipoli into a tale of noble sacrifice.

As Professor Reynolds says, children are being taught how we fought but not why we fought. And the “why” is a terrible story. In the Boer War and World War One it was for the British Empire. For the past 70 years it has been for the imperial ambitions and economic interests of the United States. Australian forces are now regularly deployed without so much as a debate in Parliament. Washington whistled, and on 12 January an Australian warship was sent to the Gulf of Hormuz to back American threats to Iran. It’s the ultimate in cultural cringe.

Jane Fonda, in red, with Lily Tomlin at the Washington rally

Appearing at a January anti-war rally in Washington, 82-year-old activist Jane Fonda spoke a truth as relevant to Australian youth as to their American peers. “Young people should know,” she said, “that all of the wars fought since you were born have been about oil.” That, she said, is why “the climate movement and the peace movement must be one”. (Fonda has been arrested five times at recent rallies; Joaquin Phoenix, Martin Sheen and Ted Danson have also been arrested.)

Australia cannot play a positive role in the world unless we refuse to be Washington’s puppet – and start to recognise our responsibility to help save the planet from disastrous levels of climate change.

Big Lie No.3 – The economy needs fossil fuel mining

On 12 January Prime Minister Scott Morrison was interviewed about the bushfires on ABC television by David Speers, the new Insiders host fresh from Sky News. The carefully-framed interview gave Morrison a platform to deliver his new line that the government recognises climate change and will do more to “adapt” to it, by deploying the defence forces, increasing back burning and doing “the best job we can” to reduce emissions – providing there would be no damage to “the economy”.

Throughout the program no one mentioned the word “coal”. It’s a prime example of what Chomsky calls “limiting the spectrum of acceptable opinion”.

One of the most dispiriting sights of recent days has been the leader of the Opposition, Anthony Albanese, rushing to articulate the sub-text for Morrison. “If you stopped exporting coal immediately,” he told media on 17 January, “then that would not reduce global emissions. There is enough displacement from other coal-exporting countries to take up that position, and that coal will produce higher emissions rather than less.”

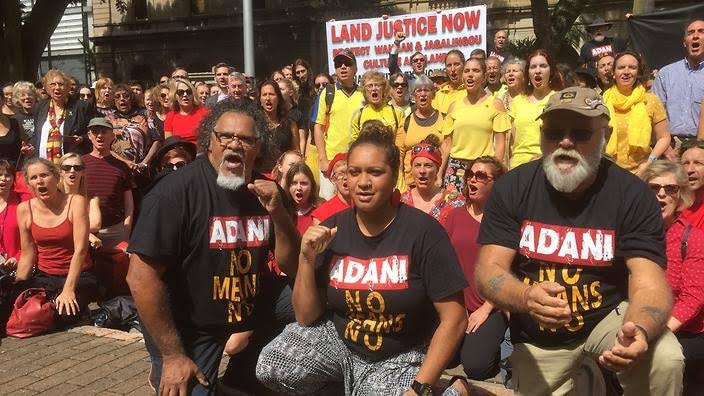

Wangan and Jagalingou traditional owners protest against the extinction of native title in the Galilee Basin

His statement is a terrible illustration of the hold the coal lobby has over Labor as well as the Coalition. The current ALP leadership appears blind to anything but the loss of Queensland seats in the recent federal election. In Queensland itself the ALP government of Annastacia Palaszczuk has prostrated itself before the climate-wrecking Adani group, giving it financial backing and even extinguishing native title in the Galilee Basin. (How can you extinguish native title? Do they believe it never was, never will be Aboriginal land? It’s little better than terra nullius.)

Neither major party appears to be considering the German solution. Germany is in the process of closing its entire coal industry without sacking a single miner. It can be done; it just takes commitment to retraining people in renewable energy industries.

The great hope to set against the antediluvian approach of the major parties comes from the generation of Greta Thunberg and Kirribilli protestor Izzy Raj-Seppings, with all their energy, intelligence and forward thinking. “We need a whole new way of thinking,” says Thunberg. “We need to start cooperating and sharing the remaining resources of this planet in a fair way.”

For Australia that means coming to terms with our history, learning from our First Nations people, ending war and becoming good citizens of the planet in mitigating climate change.

Why governments fear the arts

In every branch of the arts, excellence involves penetrating beneath the appearance to the essence of things. That’s an inherent threat to established interests, and it’s why the powerful instinctively fear creative people.

It’s no accident that the same governments that resist action on climate change are also active in attacking the arts. Drastic spending cuts by both the Federal and NSW governments undermine the independence of institutions and hack away at the smaller bodies and regional organisations that foster emerging artists.

But the attempt to suppress critical thinking is failing. There is a powerful groundswell in this country’s arts community in reaction to the bushfire catastrophe.

It’s not only that artists have been quick to come to the aid of firefighters and stricken communities. They have shown exceptional generosity: Celeste Barber’s fundraising appeal, the musicians across the country who are playing at fundraisers, the donations from actors rich and poor.

It’s above all that many in the arts community are taking a stand for climate action and political change. Russell Crowe sent a strong message to the Golden Globes. Indigenous artists call on us to nurture the land instead of despoiling it; even before the bushfires, Miles Franklin winner Melissa Lucashenko said that we need a revolution. By far the most eloquent voices raised against the Morrison government’s inaction on climate change are not those of politicians but of some of our finest Australian authors: Richard Flanagan writing in The New York Times and James Bradley in The Guardian .

There are thousands of others who do not hit the headlines. People like artist Michael Fitzjames who made himself a placard and left his studio to join the 12 January Sydney demonstration; like Lindsay Sharp, a distinguished spokesman for the Powerhouse Museum Alliance, who excoriated the federal government even as he battled to save his rural home; like my friend Kes Harper, jewellery maker of the Hunter, who took to social media to chronicle the devastation around her in Wollombi and make a powerful plea for climate action.

Thousands on the march across Australia

They are all part of a global movement. “It is not only our planet that is on fire,” writes Canadian intellectual and environmental campaigner Naomi Klein in her recent book On Fire. “So are social movements rising up to declare, from below, a people’s emergency.”

Like the first green shoots emerging from a scorched landscape, an alliance is beginning to take shape in the wake of this summer’s bushfires, as people of the most diverse backgrounds are moved, out of profound concern, to join their voices to those of the school strikers. In opposing the vested interests that threaten the future of the planet, artists and art lovers are going to have a crucial role to play.

“Rise like lions,” wrote the poet Shelley 200 years ago. And never forget: “Ye are many – they are few.”

Thank you Judith – incisive as ever.

Brilliant…..as always. Thank you ! Wish I were fitter…& OF COURSE!…. YOUNGER!….& I’d be out marching too! Can but do it now…at home…with the fingers….but remember that old saying….The pen is mightier than the sword! (Phrase taken from Tony Abbott’s profound treatise Battlelines, I believe…?)—-. Hahahahaha 🤯

Excellent article, Judith. Thank you for summarising the state of things so succinctly.

Thankyou Judith.

Powerful truths which we can only hope is catalyst to the changes needed…urgently.

Thank you for your depressingly accurate summary Judith. I have a banner of a proverb from 1546 which I made up to take to the rallies I have been attending lately: “There are none so blind as those who will not see”. It is deeply frustrating when there is so much that could be done…

Well done Judith! You’ve brought together a number of currently critical issues and shown just how interrelated they actually are. It’s great food for thought re what needs to happen next, as we grow this global movement to stop the damage and save what’s left of our beautiful world and the cultural institutions currently under attack.

So totally inspiring Judith. Martin Luther King said when building the Civil Rights Movement.. “We need a revolution of values”..yes we sure do and Artists will find a way…always.